Aesthetics of Silent Illumination

Wu-Hsiung Chen

The essay is a brief introduction to Silent Illumination as is practiced in daily life, which hopefully may encourage more people to learn to practice it.

In the analects of early Chan patriarchs, there are views very similar to those held in Silent Illumination. Not until the Song dynasty did Silent Illumination begin to be taught as an independent school by Touzi Yiqing (1032-1082) of the Caodong line. Only afterwards was the name Mozhao Chan formally proposed by Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091-1157). It thus co-existed with Huatou Chan of Dahui Zhonggao (1089-1163) of the Linji line as two major schools of Chan.

Mozhao Chan had disappeared for nearly 800 years before it was rediscovered and practiced by Master Sheng-yen during a retreat in 1967. He continued to learn more about it during his subsequent visits and studies for a Ph. D. in Japan and then teaching in the U.S. Finally in 1999 he assured himself that the Chan he had been studying and practicing for years should be Mozhao Chan, or Silent Illumination, which had been lost for nearly 800 years.

The most important method of practicing Mozhao Chan is what was described by Hongzhi Zhengjue as “knowing is so subtle but not by touching it; observing is so wonderful but not by confronting it.” When our Six Sense-organs get in contact with Six Dusts, we can distinguish, handle, accept or reject things according to our consciousness accumulated through constant learning in our life . But such knowing and observing are very limited. Silent Illumination falls into three stages. The first is “just sitting.” In the second stage, you experience oneness with the environment enabling endless inwards observation. In the third stage, you will achieve outwards and boundless observation.

Although an average person cannot achieve boundless Illumination in daily life, we can, through practice, develop such qualities of relaxation coupled with open awareness, perfect stillness coupled with luminous clarity. By dispelling scattered thoughts, we can achieve a calm, enlightened mental state naturally. There will be no conflicts or differences between you and all surrounding people, things and objects. The beauty of such harmonious integration is well worth experiencing and enjoy in our daily life.

If you are fully devoted to what you are doing and fully aware of yourself and the surroundings, your mind will, like a mirror, reflect truthfully the environment, but not fluctuate with its changes. Before tasting tea, you should give up all previous experiences and preferences and harbor no expectation, no choice, and no distinction. In this state of emptiness, your six sense-organs will ensure an open mind, enabling you to appreciate the color, fragrance, flavor and aroma of the tea in a natural manner. When you concentrate on listening to music or the sound of nature, let all sounds be heard with no choice. Finally you will lie in a state of oneness with sound, without any separation between yourself and sound, and all sounds are clearly heard. This is the state in which Arya Avalokiteshvara found herself—“all sounds are heard but they do not stay in your mind.” When you keep concentrating on walking and open your six sense-organs, you can directly observe the current situation and experience a harmonious and quiet relationship with the surroundings. We should learn to apply Silent Illumination or Mozhao Chan in our daily life to derive calmness, serenity and wisdom. In a busy and competitive climate, we should practice Mozhao Chan to calm our body and mind and experience the abundance and beauty of human life.

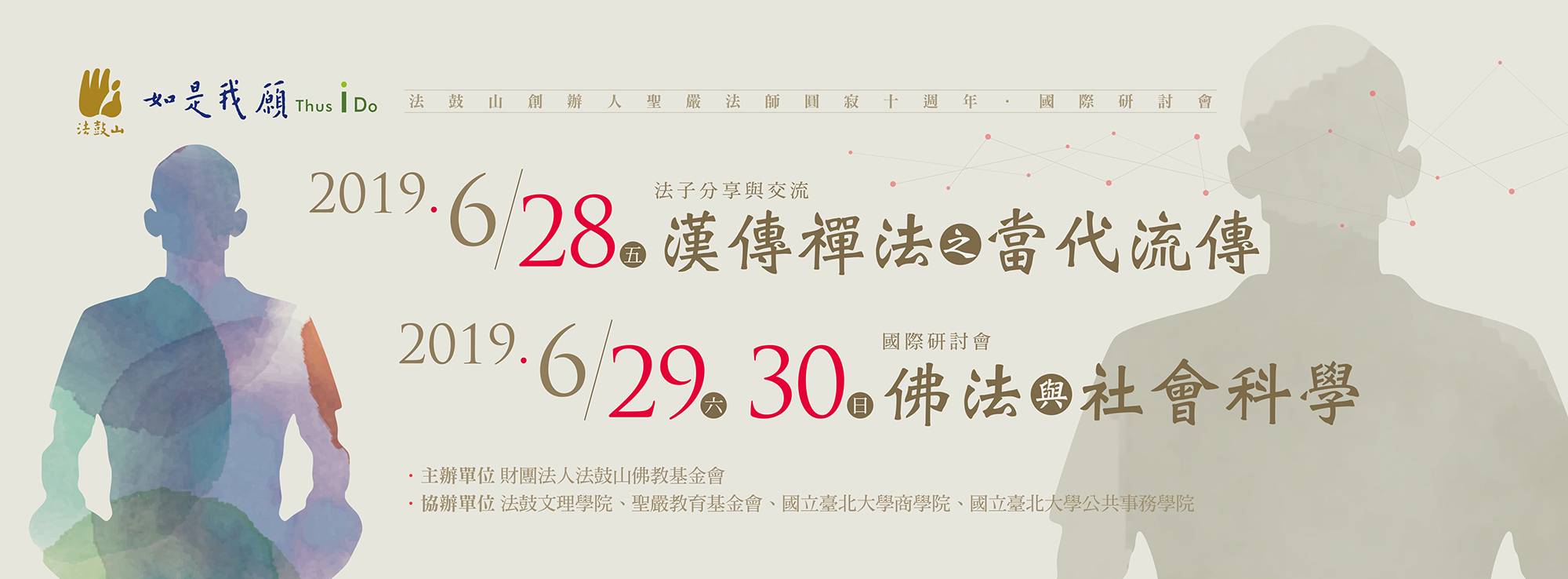

To mark the 10th anniversary of Master Sheng-yen’s passing and requite his many kindnesses, I take the liberty of writing this essay to share what I have benefited from practicing Silent Illumination myself. I hope my example will encourage more “good, virtuous friends” to join forces to expand the practice of Chinese Chan Buddhism among the public.